Understanding the Debate Over UGC’s Equity Rules

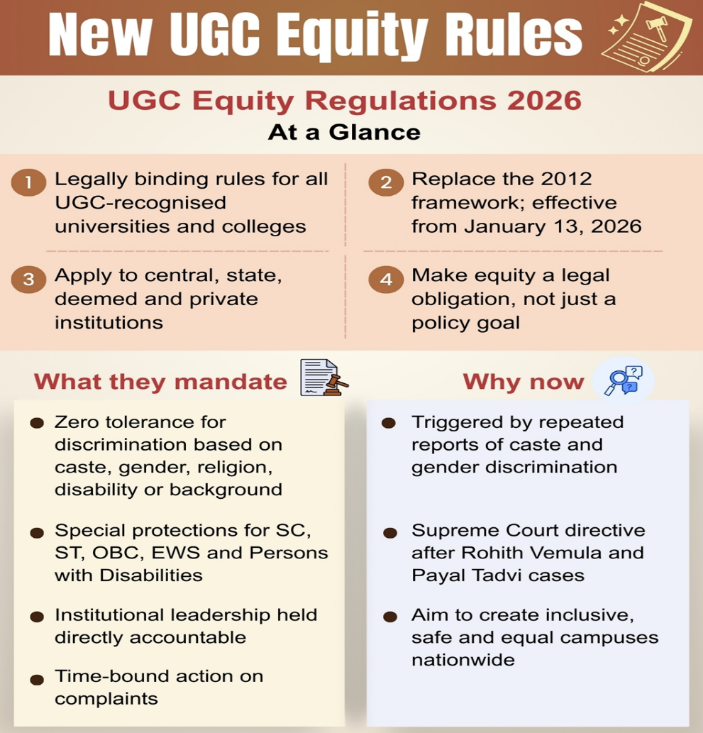

In January 2026, the University Grants Commission (UGC) introduced a set of rules called the Promotion of Equity in Higher Education Institutions Regulations, 2026. These were meant to tackle caste-based discrimination on college campuses across India and promote fairness, especially for students from historically disadvantaged groups.

But almost immediately after they were announced, the rules sparked nationwide controversy. Large numbers of students, teachers, parents, and even some government officials began to speak out. Many people, especially those from the upper caste or general category, feel strongly that these rules are not just misguided, but discriminatory against them.

Here’s a clear, calm look at the situation — why the rules were made, what they say, and why large sections of the upper caste community see them as unfair or even anti-upper caste.

What the New UGC Regulations Say?

The UGC rules aim to eliminate discrimination based on caste, religion, gender, disability, and place of birth in colleges and universities. They require every higher education institution in India to:

- Set up Equal Opportunity Centres (EOC)

- Form Equity Committees

- Operate 24×7 helplines and grievance mechanisms

- Address complaints of bias quickly and transparently

For many, the idea of tackling discrimination sounds sensible. Nearly all societies agree that no one should face unfair treatment because of their identity.

However, the way these regulations are written — especially how they define caste discrimination — has become the centre of dispute.

Why the Definition of “Caste Discrimination” is Controversial?

The core problem lies in how the law defines who can be a victim of caste discrimination:

According to the regulations, caste-based discrimination is defined only as discrimination against Scheduled Castes (SC), Scheduled Tribes (ST), and Other Backward Classes (OBC).

This means that students or teachers from the general (upper caste) category are not considered protected under this definition — even if they face bias or unfair treatment on campus because of their caste identity.

Critics argue that this is not a caste-neutral definition of discrimination. It treats one group as potential victims and others as assumed perpetrators or unworthy of institutional protection.

This selective protection is what many upper-caste students and families see as institutional discrimination. It creates a system in which one group is automatically protected, while another is excluded from the legal mechanisms meant to ensure fairness.

The Supreme Court Challenge

The controversy has reached the Supreme Court of India. A petition was filed challenging Regulation 3(c) of the new rules. The petitioner argues that:

- The definition of caste discrimination is “non-inclusionary” and unconstitutional.

- It denies protection to general category students and faculty who might face caste-based harassment.

- A truly fair system should be caste-neutral, protecting anyone who experiences discrimination on the basis of caste — not only specific groups.

- The existing setup potentially violates fundamental rights under Articles 14 (equality), 15 (non-discrimination), and 21 (dignity of life) of the Constitution.

In short, the plea says that if discrimination is defined in a way that excludes certain groups from protection, the law itself becomes discriminatory.

This is not a fringe argument — it goes to the heart of constitutional principles of equality and justice.

Why Many Upper Caste Students Feel Targeted?

Beyond legal arguments, there are deep emotional and everyday concerns among upper caste students:

-

No Protection for False Accusations

One of the biggest fears is that the regulations do not have strong safeguards against false or malicious complaints. If someone files an equity complaint, the accused student may face inquiries or disciplinary action without clear protection against false charges. Many feel this puts innocent students at risk.

This fear is heightened by the fact that:

- The rules allow complaints based on implicit discrimination — a broad and subjective term.

- No clear penalties for those who make false complaints.

- Nobody is guaranteed strong procedural protection before being labelled discriminatory.

For upper caste students, this means a single allegation — even if untrue — could have serious consequences for their reputation, studies, or even future career.

-

Equity Committees and Bias Fears

The Equity Committees the UGC wants set up on every campus are required to include members from SC, ST, OBC, women, and persons with disabilities. While representation is important, critics argue that the lack of general category representation in these bodies could lead to biased decision-making.

From their perspective, this is a structural disadvantage:

“The rules make the general category implicitly less trustworthy and remove their voice from grievance bodies.”

Many feel that committees with unbalanced representation cannot fairly adjudicate complaints that involve upper caste students.

-

Campus Atmosphere of Suspicion

Another concern is the fear of turning college campuses into zones of constant monitoring. The idea of “equity squads” or equity committees constantly watching behaviour is seen by some as:

- Surveillance rather than support,

- Encouraging a culture of accusation and mistrust,

- Reducing freedom of expression and interaction.

Students worry that innocent jokes, casual disagreements, or social interactions could be misinterpreted and treated as caste bias.

This creates a climate of fear — not peace.

-

Perception of Reverse Discrimination

For many upper caste families, the regulations feel like a reversal of equality, where one group receives special institutional protection while another group is not allowed the same safeguards.

This perception is not just emotional — it touches on the principle that laws should protect everyone equally, not only specific groups.

The petition in the Supreme Court argues precisely this: Discrimination protections should be caste-neutral and constitutional.

Comparing Past and Present Disagreements

India’s history shows that debates over caste and affirmative action are not new. In the past:

- The Mandal Commission protests in the 1990s saw massive opposition from upper caste students when reservations were increased for OBCs.

These protests were rooted in the belief that changes in affirmative policies would limit opportunities for general category students in education and employment. The current UGC controversy echoes some of these earlier fears — not about reservation alone, but about who gets legal protection and who does not.

Loyalties, Trust, and Education Policy

Another layer to this debate is trust. Even government officials acknowledge that a big reason for the backlash is not necessarily opposition to equality itself, but a lack of faith in how the rules will be implemented.

Education Minister Dharmendra Pradhan has assured there will be no misuse. But critics argue assurances are not enough without:

- Clear safeguards against false complaints,

- Balanced definitions that protect everyone,

- Procedural fairness and appeals,

- Institutional autonomy without excessive surveillance.

Without these, upper caste communities feel the rules are more about control than fairness.

Are the Rules Really Anti-Upper Caste?

From one perspective, the regulations aim to correct historical inequalities and protect disadvantaged groups — a goal many Indians support. Yet from another angle, because the current formulation excludes general category students and doesn’t protect them equally, they feel discriminated against by policy itself.

That’s why many students, teachers, and citizens are calling these rules anti-upper caste — not because they oppose equality in general, but because:

- The definition of discrimination excludes them.

- They lack access to the same protection mechanisms.

- There are no safeguards against misuse or false accusations.

- The structure places them at a procedural and reputational disadvantage.

What the Critics Want?

The Supreme Court petition is clear: the definition of caste-based discrimination should be:

- Caste-neutral,

- Inclusive of all affected individuals regardless of their group,

- Consistent with constitutional rights of equality,

- Procedurally fair to both complainants and the accused.

Many protesters also want:

- Clear penalties for false complaints,

- Balanced representation in Equity Committees,

- Protections that do not assume guilt based on identity,

- Processes that do not harm campus harmony.

Final Thoughts

The UGC’s 2026 regulations show how deeply caste still influences Indian society — even in institutions meant for learning. While the intention to end discrimination is admirable, the method of implementation has triggered concerns that the rules might create new forms of bias instead of eliminating them.

For upper caste students and communities, the fear is not just about losing privilege, but about being left without protection under the law, turned into default suspects in caste disputes, and being vulnerable to misuse of an ambiguous system.

Whether the Supreme Court reforms these rules or not, the larger lesson is this: True equity must protect everyone equally and uphold justice for all — not just a chosen few.